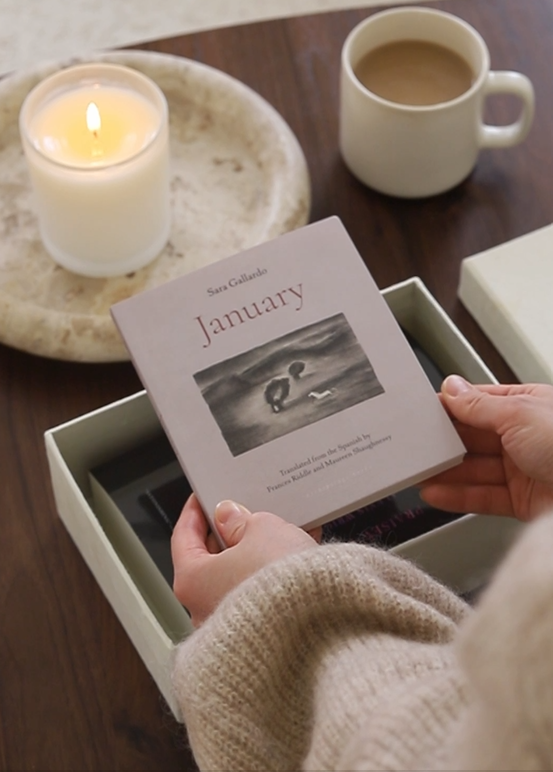

“The first Argentine novel to represent rape from the survivor’s perspective and to explore the life-threatening risks pregnancy posed, in a society where abortion was both outlawed and taboo…” Did Sara Gallardo know, when she wrote January nearly seventy years ago, that her audacious debut would be described not only as a landmark work of Argentine literature but also see its global revival in the 21st century, where it resonates rather too closely with contemporary readers? (After the Texas abortion ban and now the Alabama Supreme Court declaring frozen embryos are children, though the state legislature has since passed a law protecting IVF).

The February Book Box is truly the note on which we want to live the rest of this year. The two books, Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright, and January by Sara Gallardo, are radical, angry, tender, and searingly honest. More than anything, the novels are brave, in a way our current collective humanity often fails to be. Reading the books together is an intense experience; Wright and Gallardo are also incredibly skilled and formally inventive writers.

We’ve written about Alexis Wright here, and now, we want to talk briefly about Sara Gallardo.

A Short Biography

Sara Gallardo was born in 1931 in Buenos Aires to an upper-class family. She belonged to an aristocratic Catholic family; her great-great-grandfather, Bartolomé Mitre Martínez, was the first President of unified Argentina. She was frequently ill and spent a lot of her childhood reading.

Sara Gallardo was born in 1931 in Buenos Aires to an upper-class family. She belonged to an aristocratic Catholic family; her great-great-grandfather, Bartolomé Mitre Martínez, was the first President of unified Argentina. She was frequently ill and spent a lot of her childhood reading.

In 1950, she started her career as a journalist. She went against her father’s wishes by deciding to write for one of the country’s leading newspapers. January was published in 1958. The novel talks about abortion with a matter-of-factness; it is an additional burden in an already burdened life. The novel was influential in Latin America: “Gallardo went on a book tour to Chile, Peru, Mexico, and Cuba. Argentinean feminists, who in 2020 won the right to legal abortion nationwide during the first fourteen weeks of pregnancy still reference “January” as a turning point in the nation’s consciousness.” (The New Yorker).

She was a prolific traveler. In 1977, she moved to Barcelona, then to Switzerland and Rome, to escape state violence in her country. She died of an asthma attack during a visit back home to Buenos Aires in 1988.

Sara Gallardo’s Writing

Her writing does not fit easily into categories; nor was what she wrote about considered “proper” for someone of her gender and class. Her works were popular and critically acclaimed in the 1950s to the 70s, but went largely overlooked afterwards. Now, she is being read again. Her short-story collection, Land of Smoke, was translated into English in 2018.

If her writing is anything to go by, Gallardo was a rebel. Her first novel, though it didn’t receive much attention at the time, was written from the perspective of Nefer, a 16-year-old who is raped by an older man. The novel traces the nine months of her pregnancy. Nefer cannot name what is happening to her. But Gallardo is unsparing in her recording the hostile environment the girl faces.

Gallardo is an observer; that much is evident in her writing. Her restraint, coupled with a report of all the facts, reveal the author to be a journalist as well. She wrote several newspaper columns and essays, in addition to her five novels, a collection of short stories, children’s books, and travelogues. But it is her ability to crawl under the skin of her characters that makes her writing so moving. Even the landscape becomes a character in her stories. “Things Happen” is a great introduction to her writing.

Gallardo is an observer; that much is evident in her writing. Her restraint, coupled with a report of all the facts, reveal the author to be a journalist as well. She wrote several newspaper columns and essays, in addition to her five novels, a collection of short stories, children’s books, and travelogues. But it is her ability to crawl under the skin of her characters that makes her writing so moving. Even the landscape becomes a character in her stories. “Things Happen” is a great introduction to her writing.

The Radicalism of Sara Gallardo’s Works

Gallardo may not have explicitly referenced the political instability of Argentina in the 1960s and 70s in her works, but her works, in its depiction of wealth, class, religion, and gender, are nothing if not political. Jordana Blejmar and Joanna Page write for Cambridge University Libraries:

But it is perhaps her abiding concern for the ‘Other’ – marginalized, solitary characters, women, animals, monsters, even elements of nature – that gives Gallardo’s literature its most powerful political dimension. If her work has mistakenly been labelled by some critics as ‘anachronistic’ for her time, perhaps one reason why her fiction has been rediscovered in the new millennium is because it appears surprisingly fresh, addressing concerns relevant to our own moment: boundaries between the human and the non-human, animality; feminist and queer themes, including transvestism, sexual abuse and abortion.

Would her very first book ever be accepted by a publisher, much less translated worldwide, if she’d written it now? It is sure to be picked up by right-wing outlets, and not only her work but her whole identity would be picked apart, to be scrutinized under a microscope and sneered at. In her work, the Church responds to a victim of rape much the same way it does now. Abortion is still as (or arguably even more) controversial than ever. It is unnerving how much of January sounds current; it is equally undoubtable that Gallardo was a writer fearless and extremely skilled at dissecting society, refusing to look away. It is also deeply unnerving to ponder over the question of how far we’ve “progressed” since the 195os.

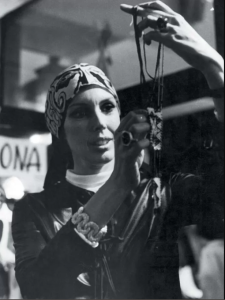

Picture of Gallardo: Source