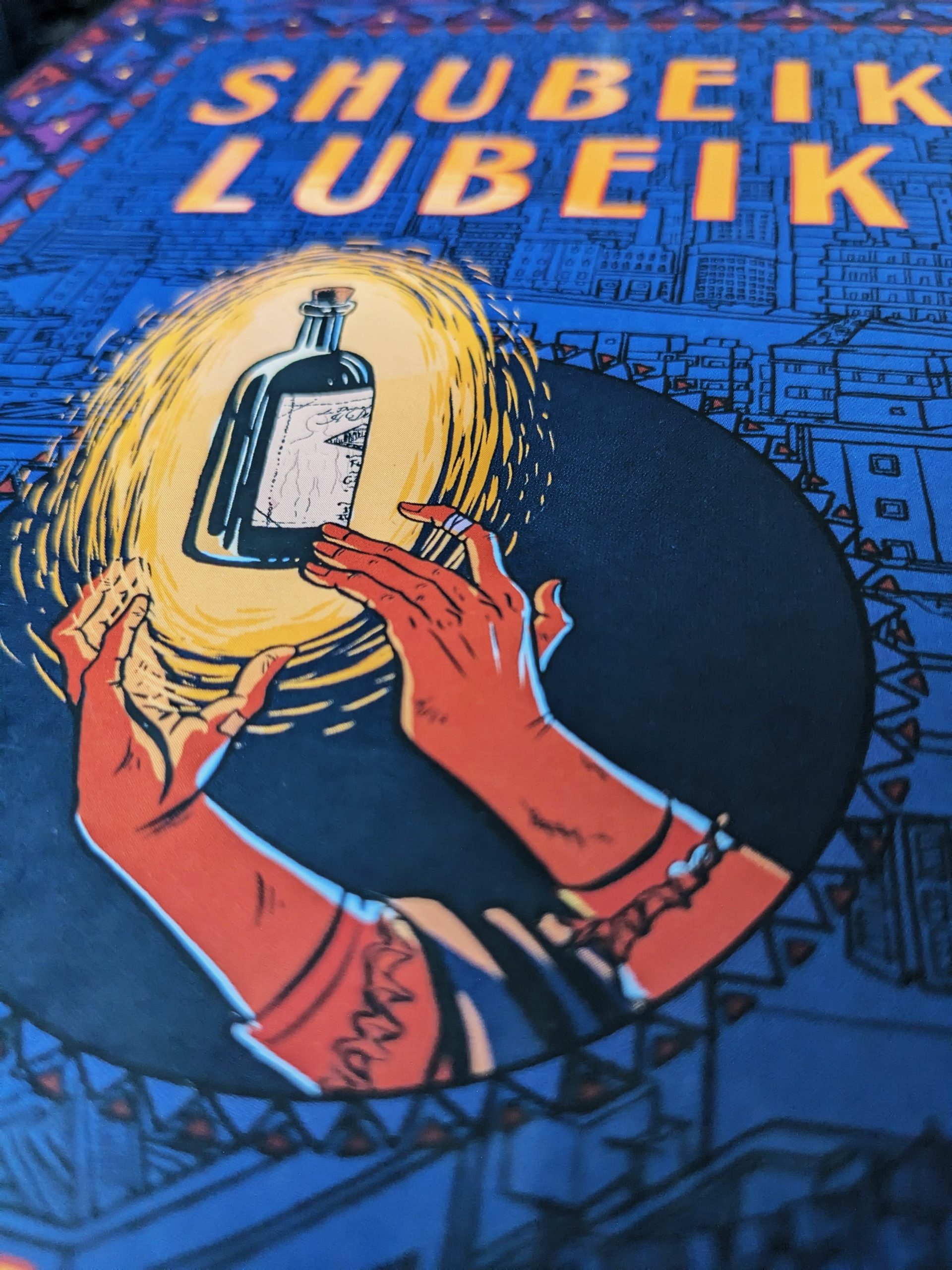

In an interview with NPR’s Ayesha Rascoe, Deena Mohamed talks about how as a child she’d spend her nights thinking of the three wishes she would make if a jinn appeared in front of her. In Arabic folklore, asking a jinn to grant you a wish is tricky: unlike God, the djinn is known to be a deceptive creature, pouncing on a wrong word or lack of detail to mess up the wish you made. Mohamed knew that when it came to jinns, one had to make a “smart” wish. And this preoccupation with wishes is at the heart of her debut graphic novel, Shubeik Lubeik, which we feature in our February Book Box:

As I devoured the book, I was struck by how Mohamed views wishes: with ambivalence and suspicion, and yet with an undeniable longing. There are no “free” wishes in the world she has created, much like our own. Even when wishes do come true, the result is often tragic: those who wished for eternal happiness, for instance, are isolated from everyone because they are always happy and thus less human. As I read Shubeik Lubeik, I started thinking about the nature of wishes. If you could wish for something, anything at all, what would you wish for? The answer, of course, changes as we do, and it reveals so much about ourselves, of our secret hopes and darkest fears, of the people we cannot bear to live without, and the faith we put in miracles. We may not believe in wishes, but we constantly wish for things.

But if you only had one wish, or limited wishes, or a wish that could fix everything in your life but also had an equal chance to backfire spectacularly, what would you ask for? Or, like in the fictional Cairo of Shubeik Lubeik, you could buy wishes, how much would you spend to afford a first-class wish that answers your most fervent prayer?

Raised in a Catholic Christian family in India, I grew up believing in a higher, supernatural power. I had an array of saints to pray to, each one dedicated to a particular cause. As students, we prayed to Dominic Savio for good marks. As good Christian girls, Maria Goretti would help us stay on the right path. And if you wanted to talk to the big guy himself, you could ask Mother Mary to put in a word. Every time we visited a new church, we were told that we could ask God for three wishes, and He would grant them. I’d spend the car ride to the church making a list of all the things I had to pray for, and ordering them according to my priorities. It was important that one wish be for someone else, because I did not want God to think I was selfish. As a teenager, my belief in the efficacy of the three wishes waned, but I would still secretly whisper three of my deepest desires whenever we were at a church, satisfied in the knowledge that only God and I knew the name of my latest crush, and now it was up to Him to make things happen if He felt it was right.

But was God an endlessly benevolent figure, granting all of my wishes and giving me exactly what He knew I needed? The number of ways you could displease God were numerous and not easily understandable. We had to listen to our parents because they knew God better than we did. On some days, God would get justifiably angry when we brawled with each other, rolling in the mud and pulling at each other’s hair. On other days, just our laughter could make him angry. There were a lot of rules to how God wanted you to be, and as you grew and adolescence hit, the rules were like a labyrinth you had to navigate, even if few made it out. It was easy to believe God was not listening to me because I was not good; that my wishes went unanswered because He was displeased with me.

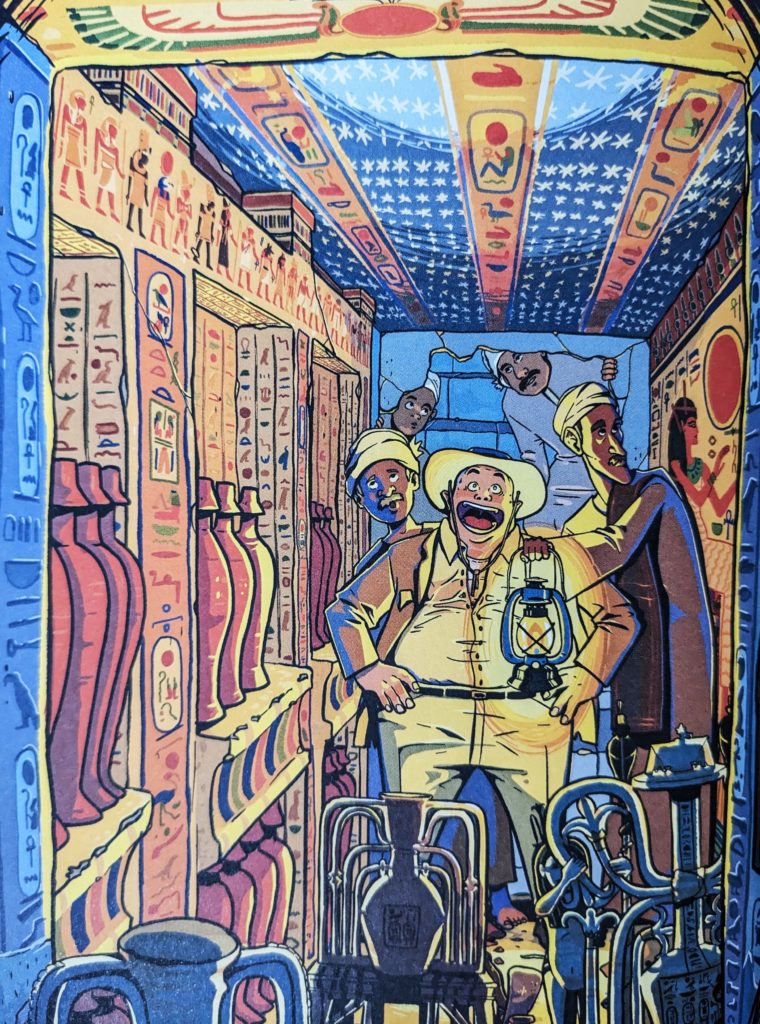

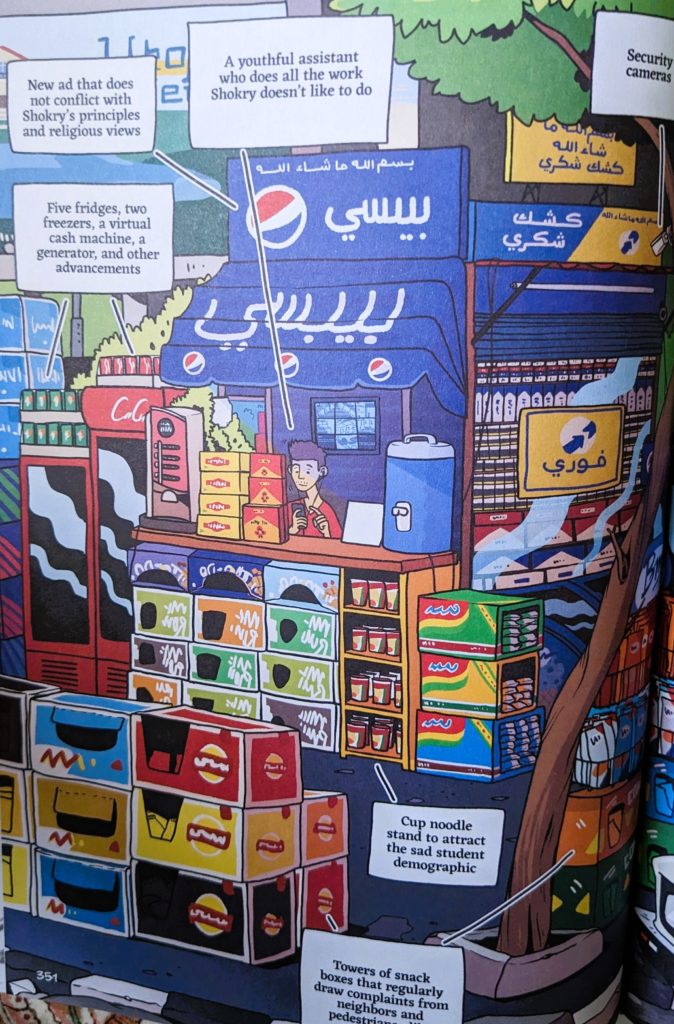

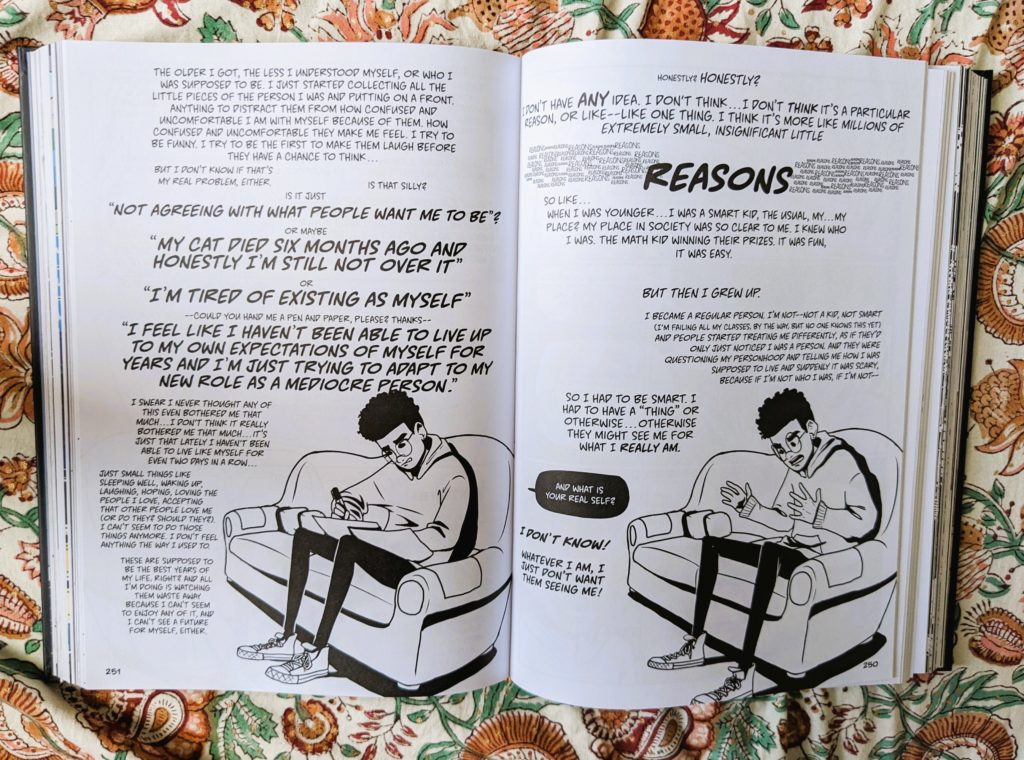

It’s precisely when things are going wrong like this, however, when you doubt your abilities to fix or overcome a situation, when you dislike yourself or your life, that you really want a wish to be granted. And Shubeik Lubeik illustrates (pun intended) this beautifully. The novel opens with a TV ad where a woman buys a wish so she can instantly lose a few pounds. As the story progresses, the wishes only get more personal, and the people making the wishes more desperate. The quiet, lonely Aziza’s wish at the end of Book I had me in tears. Nour’s debates about whether to use a wish to “cure” their depression even though they felt there was nothing really “wrong” with their life is interspersed with graphs depicting their mood and energy levels, a visual representation of how draining it can be to live with one’s thoughts. Even Shorky, who is fervently against wishes, is made to test his belief in a situation where a miracle is necessary.

Yet, all these individual wishes seem insignificant and almost meaningless when contrasted with the painfully realistic world in which Mohamed sets her story. Wishes are highly regulated, and the system makes it almost impossible for Aziza to use the first-class wish she buys. Corruption and inequality leap off the pages as much as magic and fantastical creatures do, and their power at times feels stronger than any supernatural energy. Even wishes made for altruistic reasons or for “the good of humanity” seem like sticking a band-aid on a gaping wound. In these instances, as a glowing New Yorker review of the book put it, “Mohamed’s humor often feels like a protest, as do the thick and assertive lines of her drawings.” The villains are

imperious policemen, crooked officials, and the bad temperaments of others as well as ourselves. Sometimes, she writes, “what stands between you and your wish could be a government employee with paperwork on the fourth floor.” At other times, it’s “the iron bars of an elected authority and a guard employed with your taxes.” In most situations, it’s a “mountain of money.”

But in a world as deeply unequal as our own, maybe it is only something as miraculous as a wish that can get an ordinary, often powerless, person what they want. The wish might be just a glimmer of hope in their lives, but don’t we all live for these glimmers? In the end, it is Deena Mohamed’s deep empathy and profound understanding of humanity that is the most magical element of the book (apart from her glorious illustrations! Click here for an introduction to the main characters). In a world where it is easier to lose hope, isn’t it almost supernatural if you can still live with dreams even if it they are eventually crushed, still love even if it will hurt, still try even if you might fail.