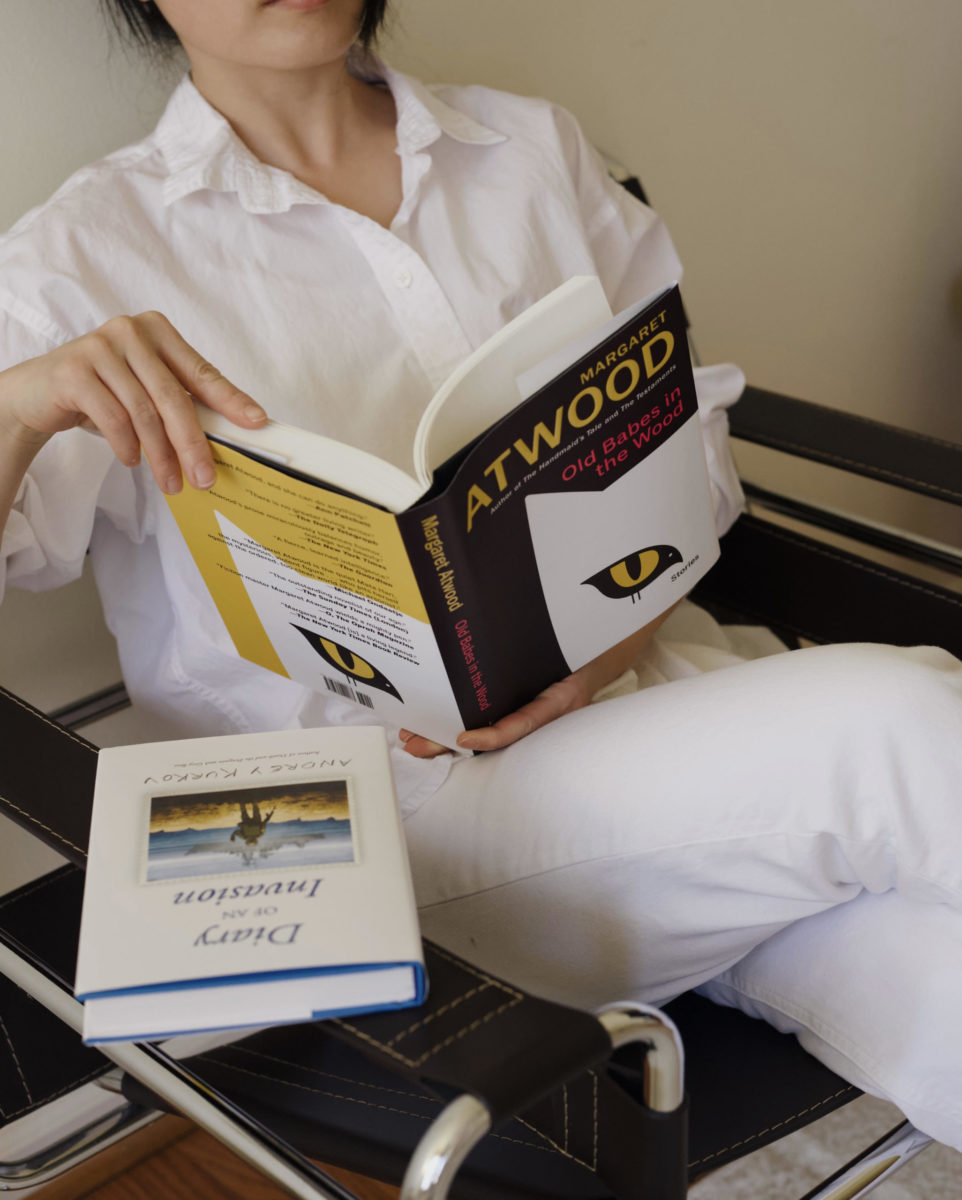

At the onset, I should say it is impossible for me to dislike Margaret Atwood. As an author of over fifty books, even she would admit that not all her works are great, but not me. I grew up reading her books and poems, and her razor-sharp wit, dark humor, and obsessions always surprise and delight me. I have a particular fondness for her short stories, with Wilderness Tips being one of my all-time favorite short-story collections. So I hope you’ll understand when I say that this isn’t an objective review of Old Babes in the Wood (which we featured in our April Boxwalla Book Box) at all, because all objectivity flies out of the window when I read anything by a person who writes like this:

“Then she wiped the blood off the kitchen floor and, after a pause, off the carrot. It was a perfectly good carrot; no need for it to go to waste.”

or

“I’ll say a word about my husband, a lovable individual who has improved with time.”

People tend to view short-story collections, especially those by already established authors, with suspicion. And there is good reason to. More often than not, such collections are a way to rehash old material or to make a quick buck off a famous name. But Atwood is truly a great short-story writer (dare I say she’s a better short-story writer than a novelist?). If you know her writing mainly through The Handmaid’s Tale and The Testaments, the Atwood beyond her most famous works could be surprising. I hope, by the end of this, I can convince you to give this (or any other Atwood) short-story collection a try.

Photo by Umid Akbarov on Unsplash

Old Babes in the Wood is a collection that Atwood herself describes as “an admittedly odd assortment of short fictions” on her Substack (which is where I discovered she could’ve easily been a comic creator). The short-story collection is divided into three sections: “Tig & Nell”, “My Evil Mother” and “Nell & Tig”.

The first and last sections are about a couple who have spent most of their lives together, sharing the same experiences and laughing together at the same things. A younger Nell and Tig were introduced in Moral Disorder, another collection of short stories, published in 2006. Here, however, the story has gotten sadder. The fictional Tig, like Atwood’s long-time partner, Graeme Gibson, is dead. Through Nell, Atwood is celebrating the life and mourning the loss of her love. A heavy wave of sadness hit me as soon as I began reading Old Babes in the Wood. Atwood’s characteristic wit is present as always, but it’s undercut by a sharp sense of loss and grief that seem to permeate all the stories.

I do not know what it’s like to share a lifetime with a partner. Growing up, most marriages seemed to be unhappy, painful arrangements in which the two parties involved resented each other but couldn’t leave. Reading Atwood, I kept remembering something an old woman told me after her partner passed away. She had had a rare, happy marriage: “Love is such a painful concept. Either you live together with someone but there is no love and your lives are hell, or there is so much love but one of you dies, and the other has to live in hell.”

I think Atwood might agree with her, but she would also laugh and probably mutter something odd – precisely why I love her. Even in stories where she seems to be (like all famous people now seem to) lamenting cancel culture and how the young don’t understand the old, such as “The Dead Interview” or “Airborne”, Atwood stops right before she begins to sound like an annoying uncle who can’t stop talking about the “good ol’ days”. There are times when I tell Atwood (in my needlessly elaborate fantasies) that she sometimes unnecessarily complicates things or seems to adopt a needlessly convoluted position in matters which seem more black-and-white, but she is always one step ahead of me. Of course, mentioning the criticism your view might provoke isn’t enough to distance the author from a character. In other people, I would’ve judged this harsher, but with Atwood, I imagine her smiling as she does below, gently reprimanding me with the assurance of an older woman: “I’m just playing around.”

But Atwood never just plays around. Her humor has always been a way to talk about injustice, unhappiness, loneliness, heartbreak, death, and any other topic that interests her. In one of my favorite stories from the collection, “Metempsychosis, or the Journey of a Soul”, her hilarious descriptions of a soul unwillingly transferred from the body of a snail to that of a woman only make the cuts the story inflicts on you deeper. In the Nell and Tig stories too, humor is interspersed with the painful realization that Tig is no more. Nell and her sister hunting for her favorite yoga pants in the title story of the collection is repeatedly punctuated with the realization that “the days of Tig” are over. In “Wooden Box”, another great story, Nell cannot bear to complete the sentence: “Now that Tig.”

There’s also plenty of dystopian and fantastical stories for any Handmaid’s fans. In “The Dead Interview”, Atwood interviews George Orwell through a medium, Mrs. Verity, while in “Impatient Griselda”, an alien tries to entertain a group of human hostages through a story. “Death by Clamshell” features a dead Hypatia, who talks about her demise in a detached and irreverent tone, asking the question,

“Ask yourself: Would you rather be memorialized as your actuality, warts and all, or as an enhanced version?” Be honest now.”

Before she laughs at how she has been historically depicted:

“What interested these painters was evidently the fact that my clothes were torn off, which allowed them to paint a naked woman in distress, always of interest to a certain kind of man.”

However, it is the stories in which nothing seems to be happening that I love the most from the collection. I’ve always admired Atwood’s skill of taking the everyday and extracting the weirdness, the odd, sad and profound parts out of it. This first struck me when I read her short story, “Hairball”, in which a woman places the ovarian cyst that has been operated out of her in a glass jar on her mantlepiece. Old Babes in the Wood has its fair share of oddness. In “My Evil Mother”, a daughter both admires and resents her mother’s behavior. The death of her cat prompts Nell to rewrite Tennyson’s “Morte d’Arthur” to “Morte de Smudgie”. All of “Airborne” is a group of aging women having a conversation, and yet you can’t stop reading.

Most of the characters in this collection are old, or “heading that way”. Atwood herself is older. Her writing is confident, and this confidence is also reflected in the loose label of “stories” applied to this collection, where the “stories” vary wildly in form and content. She is comfortable in her position as one of the greatest living writers and has nothing left to prove. Though as witty as ever, there is something about her writing in Old Babes in the Wood that feels more subdued. It is evident she is grieving. At times, I felt I was witnessing a grief that is private and not mine to see. Atwood is, above all, writing for herself. I can only be grateful she lets us have a peek.

From Rosemary’s desk

| Rosemary is the content and marketing editor at Boxwalla, with years of experience as an editor at a prominent publishing house in India. She devours books and has opinions (loves Dostoyevsky, hates Joyce) and has recently fallen in love with skincare as well! |